Current Canadian Federal Animal Cruelty legislation has its roots dating back to 1635.

1635, 1641, 1654: First known laws protecting animals

Richard Ryder writes that the first known legislation against animal cruelty in the English-speaking world was passed in Ireland in 1635. It prohibited pulling wool off sheep, and the attaching of ploughs to horses' tails, referring to "the cruelty used to beasts," which Ryde writes is probably the earliest reference to this concept in the English language.

17th century: Animals as automata

1641: Descartes

Frans Hals | Portrait of Rene Descartes (1596-1650)

The year 1641 was significant for the idea of animal rights. The great influence of the century was the French philosopher, René Descartes (1596–1650), whose Meditations was published that year, and whose ideas about animals informed attitudes well into the 21st century.

1693: John Locke argued against animal cruelty, but only because of the effect it has on human beings.

Against Descartes, the British philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) argued, in Some Thoughts Concerning Education in 1693, that animals do have feelings, and that unnecessary cruelty toward them is morally wrong, but—echoing Thomas Aquinas—the right not to be so harmed adhered either to the animal's owner, or to the person who was being harmed by being cruel, not to the animal itself. Discussing the importance of preventing children from tormenting animals, he wrote: "For the custom of tormenting and killing of beasts will, by degrees, harden their minds even towards men." This concept is fully in evidence as present in the Animal Cruelty Syndrome its signature Pathology and the links between animal abuse and violence towards human beings.

18th century: The centrality of sentience, not reason

1754: Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) argued in Discourse on Inequality in 1754 that animals should be part of natural law, not because they are rational, but because they are sentient:

Rousseau states:

Here we put an end to the time-honored disputes concerning the participation of animals in natural law: for it is clear that, being destitute of intelligence and liberty, they cannot recognize that law; as they partake, however, in some measure of our nature, in consequence of the sensibility with which they are endowed, they ought to partake of natural right; so that mankind is subjected to a kind of obligation even toward the brutes. It appears, in fact, that if I am bound to do no injury to my fellow-creatures, this is less because they are rational than because they are sentient beings: and this quality, being common both to men and beasts, ought to entitle the latter at least to the privilege of not being wantonly ill-treated by the former."

1789: Bentham

Jeremy Benthem | Courtesy National Gallery London England

One of the founders of modern utilitarianism, the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), although deeply opposed to the concept of natural rights, argued with Rousseau that it was the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, that should be the benchmark of how we treat other beings. If rationality were the criterion, many humans, including babies and disabled people, would also have to be treated as though they were things.

Bentham Stated:

"The day has been, I grieve to say in many places it is not yet past, in which the greater part of the species, under the denomination of slaves, have been treated by the law exactly upon the same footing, as, in England for example, the inferior races of animals are still. The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been witholden from them but by the hand of tyranny? Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail?"

"The time will come, when humanity will extend its mantle over every thing which breathes"The question is not, Can they reason, nor can they talk, but, Can they suffer?"

Jeremy Bentham (1781)

19th century: Emergence of jus animalium

Legislation

The first known prosecution for cruelty to animals was brought in 1822 against two men found beating horses in London's Smithfield Market, where livestock had been sold since the 10th century. They were fined 20 shillings each.

The 19th century saw an explosion of interest in animal protection, particularly in England. Debbie Legge and Simon Brooman of Liverpool John Moores University wrote that the educated classes became concerned about attitudes toward the old, the needy, children, and the insane, and that this concern was extended to non-humansFrom 1800 onwards, there were several attempts in England to introduce animal welfare or rights legislation. The first was a bill in 1800 against bull baiting, introduced by Sir William Pulteney, and opposed by the Secretary at War, William Windham, on the grounds that it was anti-working class. Another attempt was made in 1802 by William Wilberforce.

1822: Martin's Act

In 1821, the Treatment of Horses bill was introduced by Colonel Richard Martin, MP for Galway in Ireland, but it was lost among laughter in the House of Commons that the next thing would be rights for asses, dogs, and cats.

Nicknamed "Humanity Dick" by George IV, Martin finally succeeded in 1822 with his "Ill Treatment of Horses and Cattle Bill," or "Martin's Act", as it became known, the world's first major piece of animal protection legislation. It was given royal assent on June 22 that year as An Act to prevent the cruel and improper Treatment of Cattle, and made it an offence, punishable by fines up to five pounds or two months imprisonment, to "beat, abuse, or ill-treat any horse, mare, gelding, mule, ass, ox, cow, heifer, steer, sheep or other cattle.

1824: Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

Richard Martin realized that magistrates did not take the Martin Act seriously, and that it was not being reliably enforced. Several members of parliament decided to form a society to bring prosecutions under the Act. The Reverend Arthur Broome, a Balliol man who had recently become the vicar of Bromley-by-Bow, arranged the first meeting to form the society meeting in Old Slaughter's Coffee House in St. Martin's Lane, a London café These meetings were the roots of course, for the RSPCA, the first ever animal welfare society, created in the world and founded by William Wilberforce.

William Wilberforce painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence

The aspects of the cruel and inhumane treatment of cattle first outlined the Martins Act of 1822 were drafted into the STEPEHEN CODE, now Canada's criminal code This is the practically the same legislation we have TODAY, as England had in 1822.

1892 THE STEPHEN CODE

Canada's first Criminal Code was enacted in 1892 after being a pet project of the Minister of Justice of the time, Sir John Sparrow David Thompson. It was based on a drafted code called "the Stephen Code", written by Sir James Fitzjames Stephen as part of a Royal Commission in England in 1879, and influenced by the writings of Canadian Jurist George Burbidge.

1st Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, Baronet (3 March 1829 - 11 March 1894) was an English lawyer, judge and anti-libertarian writer. He was created 1st Baronet Stephen by Queen Victoria. From 1858 to 1861, Stephen served as secretary to a Royal Commission His carreer was notebale one, one in which he drafted the Indian Evidence act.

Using Jeremy Bentham's ideal of codification, Stephen attempted to get the same principles put into practice in the United Kingdom. This work became the foundation of what was to be known as THE STEPHEN CODE Intoduced into Canada in 1892 as THE STEPHEN CODE now what we know as the Criminal Code of Canada The original 1892 stipulations agianst cock fighting and inhumane treatment of cattle, remain in our Crinimal Code. Very little has changed in in over 100 years! (View the current Criminal Code of Canada.)

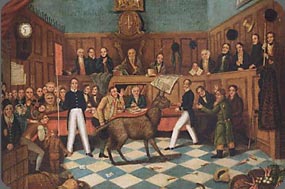

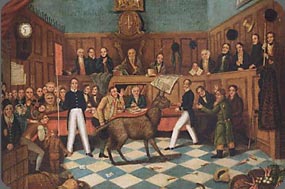

Painting of the Trial of Bill Burns, the first prosecution under the 1822 Martin's Act for cruelty to animals, after he was found beating his donkey. It is the first known prosecution for animal cruelty in the world. The prosecution was brought by Richard Martin, MP for Galway, also known as Humanity Dick, and the case became memorable because he brought the donkey into court. The painting was made at the time of the trial.

OUR SOCIETY TODAY

In 1822 Animals had an entirely different role in society!. Britain was a small country and its livelihood primarily rooted in practical farming Farm animals needed protection horses and cattle in particular There were no terms such as " companion animals" no service animals, no swine flue, no factory farming, no vets, no Animal Cruelty Syndrome with its signature pathology This language and terms of reference did not exist. All there was, were cock fights, badger baiting, dog fights and cruelty to farm animals.

The roots of animals as sentient beings goes back to 1754, roots put forward by Jean-Jacques Rousseau Animals as sentient beings is not new thinking and yet this thinking and the FACT that animals have a completely different role/place in our society, have been disregarded by our Government in their entirety!

This is shocking, absolutely unacceptable and it is going to change.

"Men have .an all but incurable propensity to try to prejudge all the great questions which interest them by stamping their prejudices upon their language."

James Fitzjames Stephen 1829-1894

Note: Some text research courtesy of Wikapedia.

Frans Hals | Portrait of Rene Descartes (1596-1650)

Frans Hals | Portrait of Rene Descartes (1596-1650) Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau Jeremy Benthem | Courtesy National Gallery London England

Jeremy Benthem | Courtesy National Gallery London England William Wilberforce painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence

William Wilberforce painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence Painting of the Trial of Bill Burns, the first prosecution under the 1822 Martin's Act for cruelty to animals, after he was found beating his donkey. It is the first known prosecution for animal cruelty in the world. The prosecution was brought by Richard Martin, MP for Galway, also known as Humanity Dick, and the case became memorable because he brought the donkey into court. The painting was made at the time of the trial.

Painting of the Trial of Bill Burns, the first prosecution under the 1822 Martin's Act for cruelty to animals, after he was found beating his donkey. It is the first known prosecution for animal cruelty in the world. The prosecution was brought by Richard Martin, MP for Galway, also known as Humanity Dick, and the case became memorable because he brought the donkey into court. The painting was made at the time of the trial.